What Else Does Emmanuel Perry Need To Prove?

The creator of Corsica Hockey weighs his options after spending the past two-plus years doing private analytical work.

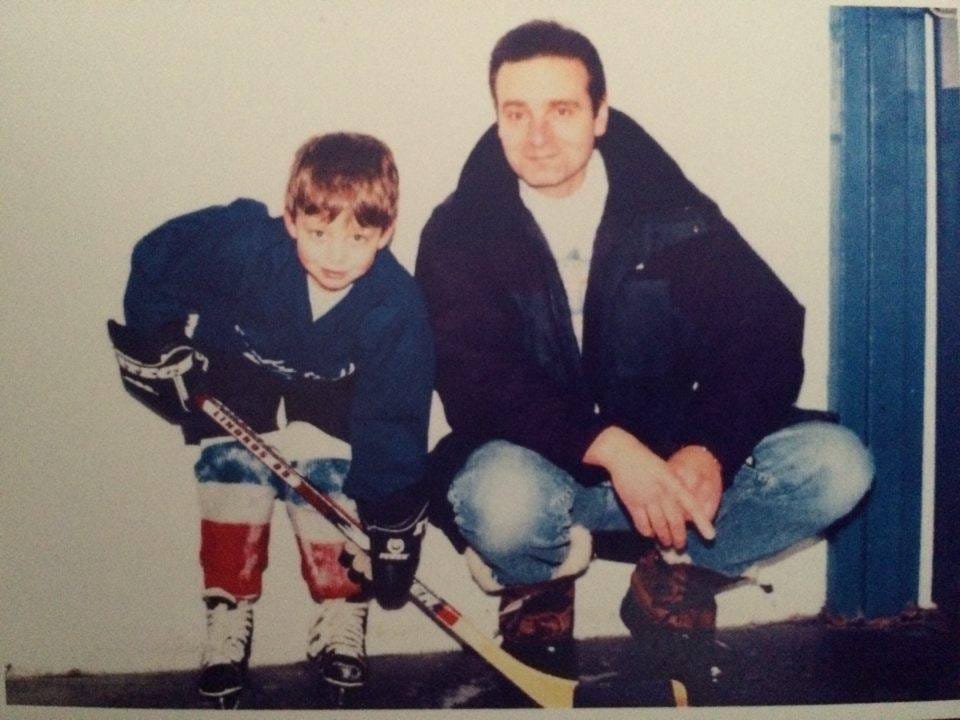

On the eve of his 28th birthday, Emmanuel Perry recalled his salad days in hockey analytics.

“I remember reading about Corsi and not knowing what it was," Perry said. "It’s funny, because I was studying math at the time, and before I knew what Corsi was, I had this idea that it was going to be over my head. I was like, 'Oh, I’m not even going to try to understand this.' It turns out to be exceedingly simple. And once I learned what Corsi was, I thought this actually makes sense. Maybe this isn’t witchcraft."

Indeed, hockey's metric for shot attempts did not baffle Perry. Nor did the zone entry and exit data Perry soon started collecting after he read about the tracking research done by Eric Tulsky and Corey Sznajder. Perry also grasped "Competing Process Hazard Function Models for Player Ratings in Ice Hockey", an academic paper that Sam Ventura, Andrew Thomas, Shane Jensen and Stephen Ma published on an early version of their WAR (Wins Above Replacement) metric. In the span of a few years, Perry absorbed all of that and also figured out how to build his own hockey analytics site and models for NHL player evaluation, real-time expected goal totals and prospect projections.

With a robust and readily available portfolio of public work, Perry became one of the more prominent figures within the analytics corner of the hockey community. Often known only as "Manny," he built a healthy following of fans and media members through Twitter and his website, Corsica. Offers for private analytical work came his way. And he did it all without a degree -- Perry studied science and math for three years at McGill University before dropping out.

Private work led Perry to keep a lower profile in the hockey analytics community during the past two years. That might change soon, though.

"There are so many people that do this now," Perry said. "You have to provide something different or do something at a very high level. There’s nothing that prevents me from building a strong enough resume or portfolio that it overturns the fact that I don’t have a degree, but I’m certainly not there yet. That gets back to me working publicly and building that portfolio. I sort of lost a couple years of my best work that now I can’t really show anyone, just by working privately.

"I think I need to get some clarity on what my next steps are. I’d like to get an opportunity with a team, but you don’t know if or when it’s going to come. Part of me wants to be patient. I might have to get back to doing public work. I think at a certain point, I might need to remind people that I can do this. And that’s fair. I haven’t been doing work publicly for quite some time. When I do share stuff, it’s half serious. If no one is going to give me a chance, I do think I have to take a step back and sort of build up my own worth again. But it doesn’t have to be in sports. I’m more than open to working in other fields. I’ve been doing some financial stuff on a freelance basis, building stock trading models. That stuff is all cool. I just need to find a way to sell myself, I guess."

"Those projects that I'm really passionate about are few and far between"

When he began to ponder his choices for a major at McGill University, Perry initially favored biology.

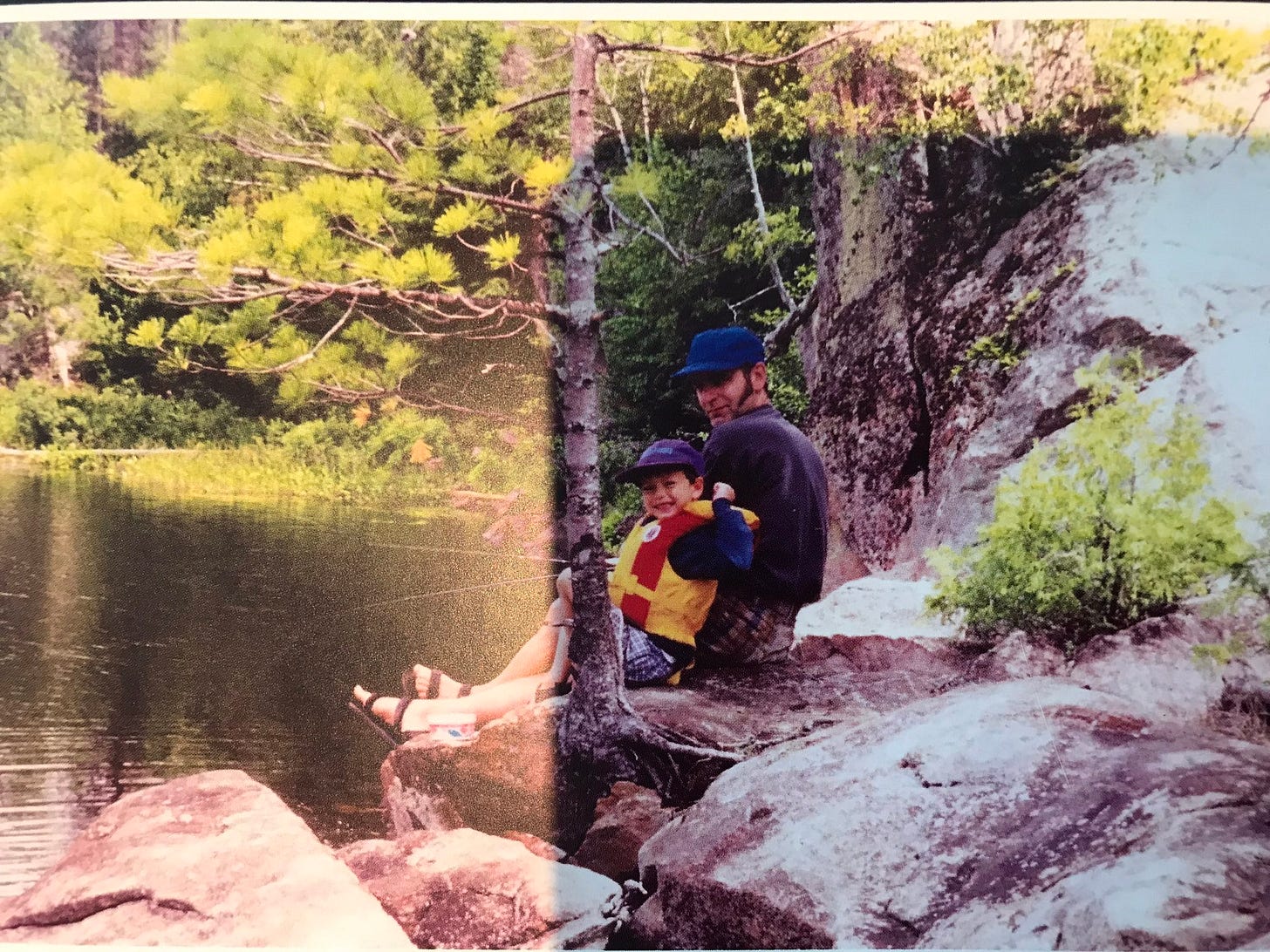

The choice made sense on the surface. Perry's father is a professor of biology at the University of Ottawa and a member of the Royal Society of Canada. His mother works in the forensic science department of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

Perry soon found himself asking questions that other classes and fields answered.

"To me, it was about getting to the source," he said. "Studying biology, at a certain point, you realize it's all just chemistry. Then when you start to study chemistry and you learn about atomic structure and quantum mechanics, and you think, oh, this is all just physics, actually. Then you study physics, and you realize you need to know a lot of math, and you're like, 'Everything is math.'”

Perry's desire to dissect and thoroughly understand subject matter transcended academics. Consider his teenage enthusiasm for fishing.

“I took it to a different level, where I was looking up fishing videos on YouTube and shit, and I was looking at different lures and stuff," Perry said. "I wasn’t happy just going fishing and having fun. I was thinking how do I get better at this? How do I get better at fishing when I’m not fishing? I was learning as a hobby. That was kind of a weird one."

His interest in fishing waned. So did his commitment to his college coursework, even though he found the concepts in sciences and math intriguing. He increasingly cared more about hockey analytics and less about his classes.

"When I become really obsessed with something, it’s easy for me to just go all out and spend all of my time learning about it," Perry said. "Even when I’m not at my computer working on something or actively studying something, it’s at the back of my mind. Sports analytics was one of the few things that hasn’t left me.

"I’ve always had the ability and potential to learn things, but I’ve very rarely been properly motivated. School was an example of that. … In hockey analytics, at times when I was doing public work, I was putting a lot of work into it, and that’s what resulted in Corsica. Or when I published a paper about my K metric, which was a precursor to the WAR model that I published. Those took a lot of time. But those projects that I’m really passionate about are few and far between.”

"OK, I sort of have a responsibility to be on the cutting edge."

Perry cited Eric Tulsky's submission to the 2013 MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, "Using Zone Entry Data To Separate Offensive, Neutral, And Defensive Zone Performance," as his first hockey data muse.

"The idea that you could sit down, watch a game, record information, and no one else was doing this, so it was new — I think I found that really exciting," Perry said.

For a little more than a season, he tracked the Ottawa Senators and shared his findings on a site he ran, Senstats. He wanted to do more though, and through War On Ice, he found an opportunity.

Results from a player similarity calculator Perry developed in R and published online caught the attention of Sam Ventura. Ventura and the other War On Ice co-creators had accepted NHL analyst positions and needed individuals to step in and keep the site going. Perry joined a small group of people entrusted with the task.

“It turned out we didn’t have enough time to really make that happen," Perry said. "Not only did they want the site to survive, they wanted a bigger, better version. They had some full-stack developers trying to convert things into basically an entirely new site, and we just didn’t have the time. But throughout that process, I was learning a lot of R, a lot of Shiny, and I was looking at a lot of their War On Ice code and learning how they did things.

"When War On Ice shut down, I was like, 'What’s the next site, who’s going to do this?' And then no one really did, at first. So I thought, OK, I can make a shitty version, and that’ll hold a spot until someone else can come along and build a good site."

Contrary to Perry's description, Corsica served as far more than a short-term placeholder. It became a destination for the metrics data-savvy hockey fans knew they wanted, plus a few that initiated new types of discussions.

“Dawson Sprigings was the one, to me, that brought (expected goals) into hockey," Perry said. "Plenty of people did shot quality stuff before that, but Dawson brought xG to the people that I was interacting with on Twitter. They were now using xG in their lexicon, and that was because of Dawson. What I wanted to do was put xG on a website, and now have that data public. So not just have Dawson be like, per my xG model, this and that, and then have people retweet it, but have anyone be able to access anyone’s xG numbers. That was a big motivator.

"When it comes to building new metrics, I think that just came naturally from getting some sort of validation from people who thought my work was at least acceptable. People were using Corsica. Journalists would cite Corsica. I thought OK, I sort of have a responsibility to be on the cutting edge.

“Whenever I put anything out there, I always have a fear that someone is going to be like, ‘This is bullshit. You don’t know what you’re talking about.’ I think that’s always going to be there. But I believed in the results that I got, for sure. I think the results I got from the K model had just the right amount of unintuitive results, in the sense that I found out new things. Not that that should ever be your goal in producing a model like this. Certainly I would’ve had more concerns about publishing if I put a model out there that said like fucking Zac Rinaldo is the best player.”

"I also always felt that the War On Ice WAR model was severely underappreciated. Like criminally so. You think about it — we’re still having discussions about should we be using WAR in this instance. They published that five years ago, and there’s still people that don’t want to use WAR, for whatever reason. So they deserve a lot of credit for that. And I think what led to me wanting to design a metric like that, an all-in-one player evaluation metric, was no one really used this WAR thing, and it was dope. … At the very least, I could show people my ideas, and then have smarter people be like this is interesting, but I would’ve done it this way."

"That self-doubt and imposter syndrome starts to subside and give way to little seedlings of confidence"

Anyone who follows Perry on Twitter now is likely to see retweets from his latest public creation, @mlb_big_boomers, a bot with a bio that reads "If a ball is hit or thrown well, I'll tweet about it."

Sometimes Perry also shares snippets of data from NBA player evaluation models he puts together.

"Against my better judgment, I don’t think of my Twitter account as like a selling point for myself," he said. "I think that bridge has been burned. Anything I put out there on Twitter is usually just for fun."

It's not necessarily the larger data sets that drew Perry to other sports. But the NHL's game data isn't pulling Perry back to hockey either.

"The public hockey play by play that we’ve been mining for over a decade doesn’t have that much juice in it," he said. "There definitely are diminishing returns. In the early going, if someone made a breakthrough, it was like this huge leap forward. Now breakthroughs are happening, and we’re getting small improvements to existing models or discovering things that might change things a little bit, but not that much. People have been saying this for a long-ass time, so I’m not bringing anything new to the table here, but there’s truth to when people say it’s going to take some new data for us to have new findings."

That reality requires Perry to confront the question that has loomed over him for a while now: Will a professional sports team -- NHL or otherwise -- hire him so he can tackle tracking data, biometrics and anything else that's withheld from the public?

“It is something I do want to do," Perry said. "In the past, I haven’t always been sure whether that’s something I want to do. When you talk to teams, everyone talks the talk about being open to appreciating analytics and your input will be valued here. But from the outside looking in, I don’t see many teams walking the walk. For the most part, I don’t see much acceptance, and I know that’d be frustrating for me if I were in that position. But lately, I think it’s almost a responsibility to be in a position to be able to change that.

"At the time (of Corsica's creation), I still felt like I had to prove that I belong in this space. Now, after having experienced the validation of being paid for my work for several years, that self-doubt and imposter syndrome starts to subside and give way to little seedlings of confidence."