Getting Abstract with Micah Blake McCurdy

Learn why the creator of hockeyviz.com generally prefers to serve the public rather than an NHL front office

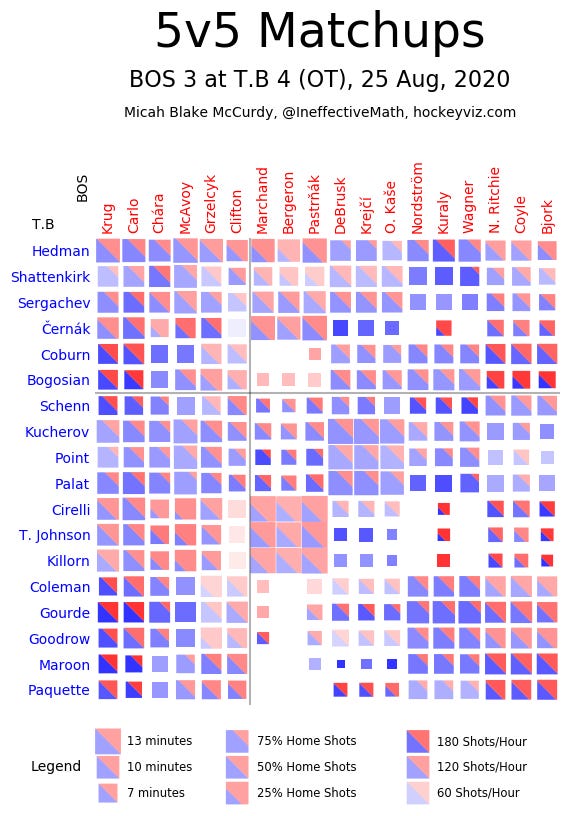

The 146 pages of Micah Blake McCurdy’s doctoral dissertation contain several visuals that, stripped of notations, might look appropriate somewhere on his oft-cited and celebrated website, hockeyviz.com.

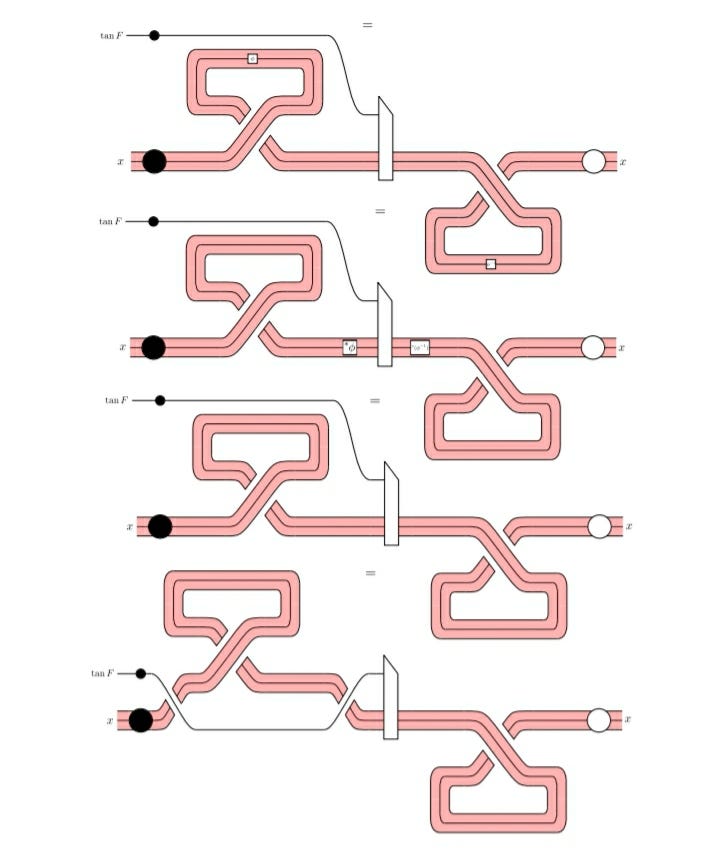

On page 65, for example, there's an oblong graphic with a relatively sparse middle section, boxed areas at each end and lines with arrows running north-south along the wings — a mathematical proof that could pose as a puck tracking sheet.

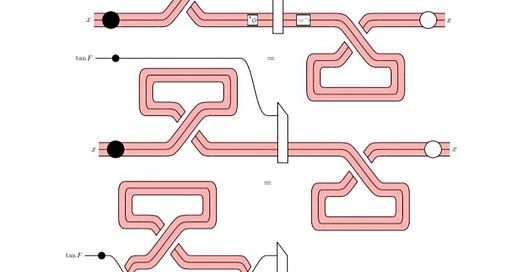

And on page 119, there are a series of looping paths, with a puck-like black dot at one end and a blank white dot of the same size at the other — a derivation that might double as a passing sequence.

McCurdy published his dissertation, “Cyclic Star-Autonomous Categories and the Tannaka Construction by Graphical Methods,” at Australia’s Macquarie University in 2011 with no plans to make a living through hockey. He wanted a full-time professorship in mathematics.

“Part of why that visual approach came out when I was doing math and still comes out now in hockey is that other approaches don’t stick in my mind properly,” McCurdy said. “I don’t learn well any other way, so it’s a great convenience to me that it seems to resonate with other people.”

With a Twitter following of more than 31,000 via @IneffectiveMath and a membership-driven, ad-free hockey website that grosses almost $80,000 annually in revenue, McCurdy is a rare breed. He shares working drafts of new visualizations with the world, unafraid to receive criticism or see his idea stolen by someone else. He has declined full-time positions with professional hockey organizations, although he did contract work for four of them. And he aspires primarily to teach about hockey with minimal reliance on words and numbers.

“You don’t have to get it right the first time”

Long before McCurdy spread the gospel of hockey analytics, he watched his father share traditional sermons.

By the time McCurdy turned 11 years old, his family had moved from Canada to Scotland to Romania as his father earned a doctorate in theology and pursued work as a missionary and minister.

As an adult, McCurdy faced a similar set of career circumstances. He and his wife went from Canada to England, where McCurdy acquired a Master’s degree from the University of Cambridge, and then continued on to Australia for his doctorate in mathematics. On the other side of the world from Nova Scotia, they also set in motion plans to start a family, only to realize their limited healthcare coverage and modest income would likely leave them bankrupt if complications arose during childbirth. So they returned to Halifax, where McCurdy's parents lived.

They now have two kids.

“One of the unwritten rules in mathematics is you can always get work, as long as you’re prepared to go where the work is," said McCurdy, whose only full-time professorship offer came from a university in Pakistan.

"For the longest time, I didn’t consider getting a Ph.D to be some sort of intellectual thing. … That’s just what I needed to do to get the job I wanted."

McCurdy's Twitter handle derives from a friend who jokingly described himself as an "ineffective workaholic." The name used by McCurdy reflects his self-deprecating sense of humor and a bit of the sting that accompanied his career path. His relationship with mathematics helps him make sense of far more than statistical models and esoteric proofs.

“One of the things you realize — math is just generally great at this — is you can initially have no idea what’s going on, and later, you will know," McCurdy said. "You don’t have to get it right the first time.

"It’s not exactly humility as it is more of a stubbornness, where you say to yourself, it’s OK, I’m going to get stuck into this, and I’m going to do my best on this, and I’m going to present it with a certain quality of confidence. And if I’m wrong, I’ll just get up off the mat and go again.

“That professional breeziness has served me extremely well, especially because there’s this constant tension when you’re doing quantitative work in hockey between how much certainty you want to present and just how much randomness and wildness there can be. You don’t get to be that certain when you’re talking about humans, least of all humans doing athletics at extraordinarily close to equilibrium situations where people are doing their very best.”

“The rewards of team work didn’t feel like rewards to me.”

McCurdy's desire to teach mathematics persists in Halifax, which is home to six public universities. He's a part-time professor. He's no longer sure a full-time position suits him.

“If somebody a few years ago said they want me to move to Manitoba and they’ll give me a full-time math position, I would’ve said ‘It’d be lovely if you can accommodate this hockey side project of mine.’ And if they put their foot down and said no, absolutely not, that would’ve been the end of hockeyviz,” McCurdy said. “If someone now were to say ‘We’re going to give you a full-time job but you have to give up this hockey thing,’ I’d say ‘Nope, go jump in a lake. You can find some way to accommodate it while I teach, or you can go away.'

“It’s not that the work is any more satisfactory. In fact, it’s the same amount of a lot of fun as it always has been for me. ... Being able to make even a little bit of money this way makes it very easy to say no.”

Professional teams in need of analysis pay too, of course. During hockeyviz.com’s early days, McCurdy supplemented the site’s revenue with consulting jobs. He quickly determined that while he enjoyed partnering with the sharp minds employed full-time by NHL organizations, he wanted to share his work with larger and more diverse audiences, and he wished to follow his own curiosities, not those of general managers and coaches.

“The penalties of having to keep things secret just felt against my instincts as an educator as well as my social instincts,” McCurdy said.

“I prefer to have a little bit of distance. ... My angles are always going to be a little more abstract just because of my personality and my training.”

McCurdy’s appetite for abstract concepts helped to popularize some of the ideas pushing hockey forward, including isolated player and coaching impacts and Gold drafting, which would reward teams that accumulate wins after falling out of postseason contention.

The almost daily deluge of positive feedback on Twitter matters a great deal to McCurdy. Mathematics as an industry often leaves scholars waiting years if not decades for validation, he noted. Maybe his dissertation will make an impact somewhere down the line. But until then, he’ll educate through the platforms available to him and try to serve as one of the sport’s most accessible academic stewards.

“Weird as it is, I think about Twitter as my workplace,” McCurdy said. “When the issues are more relevant to areas of concern, like scholarship in hockey stats, I do feel that urge to speak up a little bit more and to be a little more aggressive, even though it’s not in my nature, just because I know that criticism to some extent will bounce off of me, where it won’t bounce off of a lot of other people.”

“Surrounding yourself with beautiful things”

When Kevin Kan (@datarink), renowned for his Atari-like animations of play-by-play hockey data, joined the Carolina Hurricanes as a data analyst in August of 2017 and, with rare exceptions, stopped posting his visuals on Twitter, requests for clever new designs flowed to the hockeyviz.com inbox.

McCurdy admires Kan’s talent and originality far too much to try replicating the style. But he also considered himself on a slightly different quest with the data.

“Stylistically, there are times I can’t do what he does because I can’t make the same choices,” McCurdy said. “He has a style which is minimalist to an almost extraordinary degree, and it’s very, very difficult to do, which is part of why I respect it as much as I do. But if you’re going to take that approach, one of the things you have to come to terms with is you’re going to have less information to actually convey."

In the section of Patreon that presents the pitch for hockeyviz.com memberships, McCurdy wrote his "graphs, charts, and articles show what happened, suggest what will happen, (and) show us how we should think about hockey." It does not mention the immense volume of visualizations he produces, nor does it reference the elegance present in nearly all of his work. And that's fine by McCurdy, whose aesthetic motivations are mostly internal.

“If you get into the habit of making things just right and the way you like them, then even if nobody listens and nobody cares about zone starts or whatever the topic is, you still get the benefit of surrounding yourself every day with beautiful things," McCurdy said. "Some days, of course, the essence of research is that you fail all the time. You have ideas and they don’t work, again and again and again. One of the few defenses you can have against that sapping your soul away is by being able to say, well, at least as I do it, it’s going to look nice.”